Systems Thinking

Revealing the interconnectedness of urban heat islands

The urban heat island effect is a serious issue that is facing metropolitan areas. As population growth continues to rise, living conditions and environments have and are changing to accommodate those who are moving into urban areas. The natural vegetation that once thrived in these locations is replaced by asphalt and concrete for various roads, buildings, and structures that are deemed necessary for the human population. As a result, these surfaces are absorbing heat from the sun, rather than reflecting it, which causes the overall temperature of urbanized areas to be much higher – upwards of 20℉.1 To date, most of the research regarding heat-related mortality from urban heat islands is done in the United States and Europe, however as developing countries begin to move towards urbanization, more studies must be conducted on the impacts faced on these individuals to reveal the larger dimensions of the problem at hand.2 Urban heat islands are created by and sustained by us, Homo sapiens, therefore it is the responsibility of our species to recognize the problem, determine its negative impacts, provide potential solutions to the problem and describe potential barriers. For this section, the application of systems thinking will be used to discuss the human responsibility of urban heat islands and articulate the problem in a new and different way that reveals the range of choices available that are sustainable.

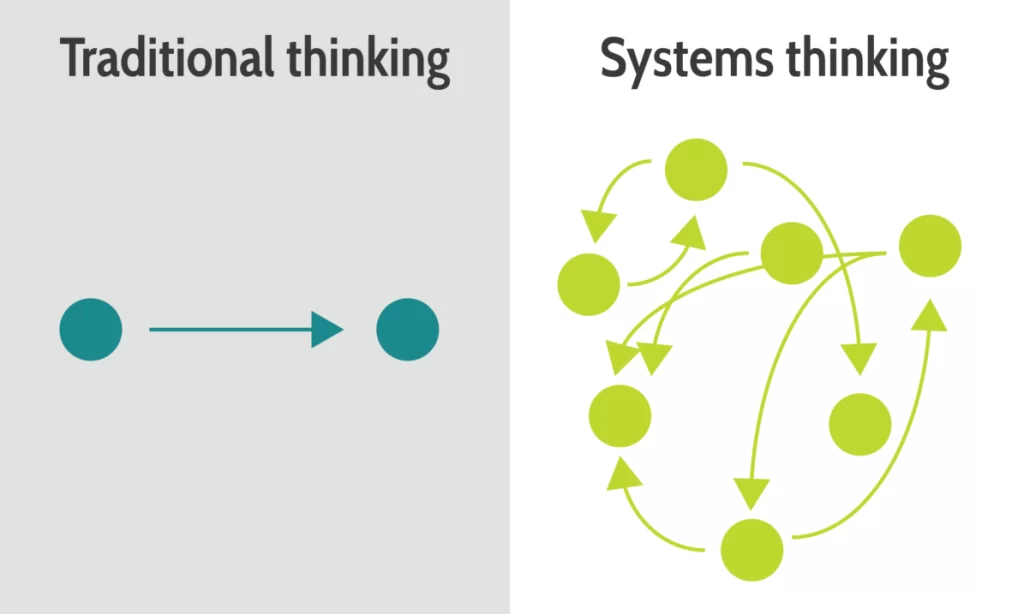

Systems thinking is an approach to problem-solving that looks at an overall system as having interrelated parts, shifting from a linear to a circular mindset. Unlike other forms of thinking, this approach is more holistic and is beneficial for problems that are much more complex. Systems thinking, for example, would not be necessary for the event that your car battery stopped working. The linear approach would assume that the battery be replaced and then the car would work. In the issue of urban heat islands, systems thinking is necessary due to the various relationships, boundaries, and perspectives that are involved.

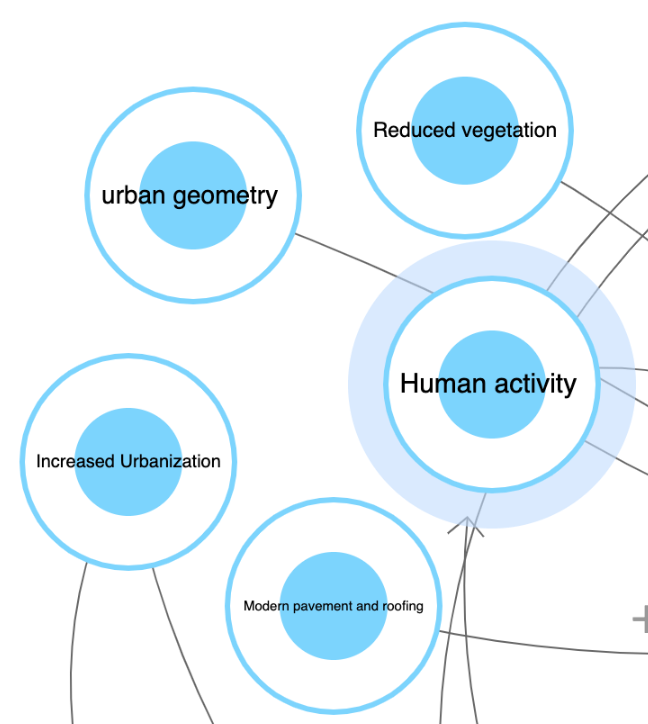

The first step to systems thinking is to describe the causes of the problem. In figure 1, various causes (blue circles) of urban heat islands are addressed including reduced vegetation, increased urbanization, urban geometry, modern pavement and roofing, and human activity. All of these causes are directly associated with the urban heat island effect because they increase the absorption of the sun’s heat and reduce how much heat is released, which leads to temperature rise. Humans play a direct role as they move into urban environments which increases the population in one place. As the population grows, more houses, roads, and buildings for a functional society are being established, but these areas are designed without taking into account how they may impact the temperature of the area.

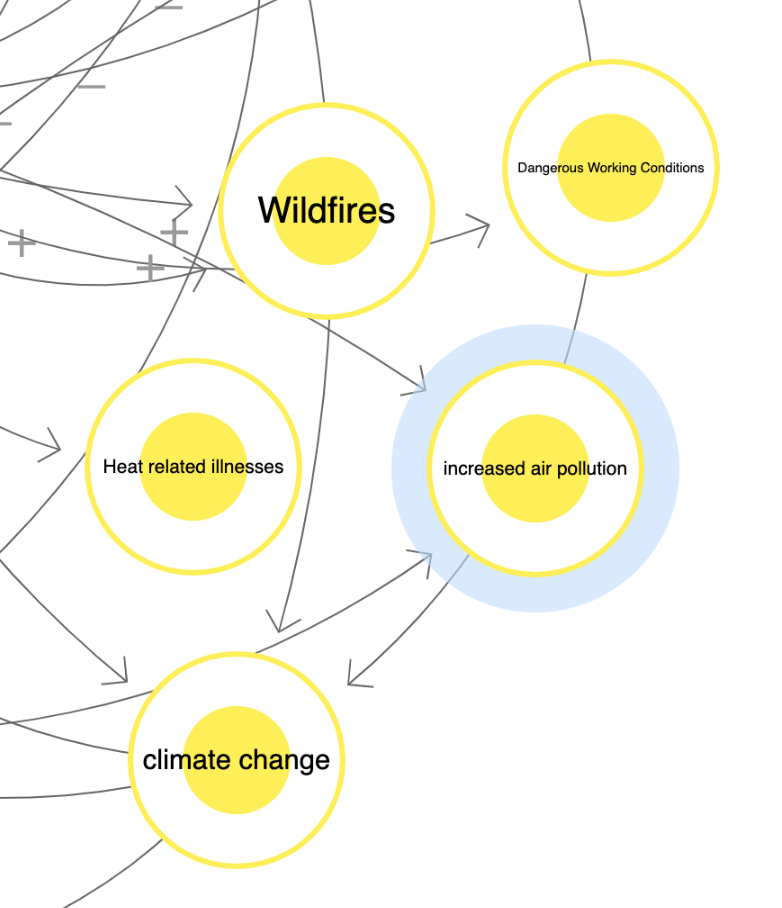

Urban heat islands have many negative impacts (yellow circles) on both humans and the environment. Extreme heat is likely to cause wildfires as the area gets dry and trees are more likely to catch on fire. As more wildfires occur because of urban heat islands, more carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere which contributes to climate change. Human populations also contribute to climate change in a heat island setting as more air conditioning is needed to cool buildings that are suffering from the increase in heat. More air conditioning means more electric use and electricity is mainly generated by fossil fuels which contribute to climate change. Furthermore, urban heat islands lead to increased levels of air pollution which is harmful to human health, and excess heat causes various heat-related illnesses and dangerous working conditions. In 2019 alone, there were 356,000 deaths related to extreme heat which statistically models the significance of addressing heat right away.3 All of these issues are interconnected and directly related to heat islands.

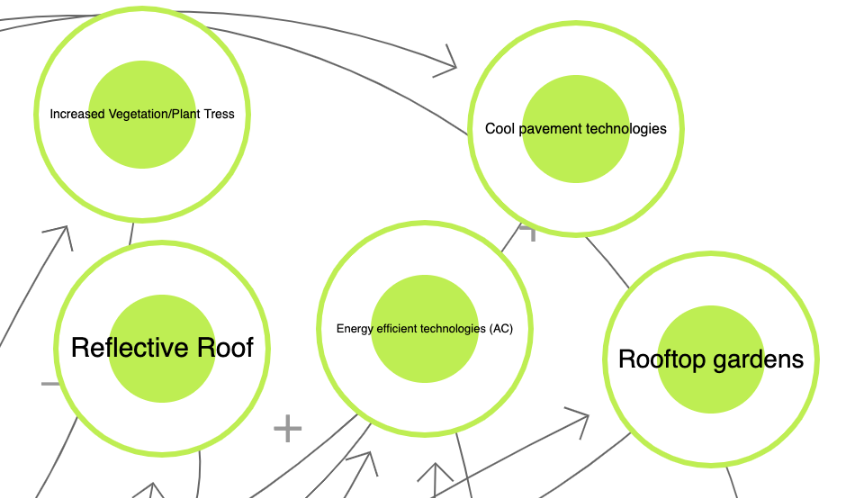

There are some potential solutions to addressing urban heat islands (green circles). One solution could be to increase vegetation in urbanized areas with an attempt to return some of the green spaces that were originally removed during its construction. Vegetation will naturally absorb and release heat and provide shaded areas for individuals, such as workers, to escape from the heat. Potential rooftop gardens could also be effective at removing heat from the air, providing shade, and reducing the temperatures of the roof. According to the EPA, green roofs can have temperatures of 30-40℉ lower than conventional roofs and this could lower city-wide temperatures by 5℉.4 If green roofs are not aesthetically pleasing to the public reflective or cool roofs with high thermal emittance could work as an additional replacement to conventional roofing materials.5 Another potential solution, which also comes from construction, is the development of cool pavement technologies. If you ever watch the snow clear naturally, you will notice that areas with green spaces hold the snow much longer than paved parking lots and that is because pavement absorbs a lot of heat. During the summertime, conventional pavement can reach temperatures of 120–150°F which is dangerous for human health, therefore it is important to consider redesigning pavement choices.6 The final solution that I would like to discuss is energy-efficient air conditioning. As discussed earlier, air conditioning use will continue to increase as the temperature rises, therefore it would be beneficial to reduce the carbon impact from air conditioning use by making them more energy efficient. This would be a practical solution; however, it would be more efficient to lower inside temperatures by using vegetation and structure cooling as opposed to continued emission technologies.

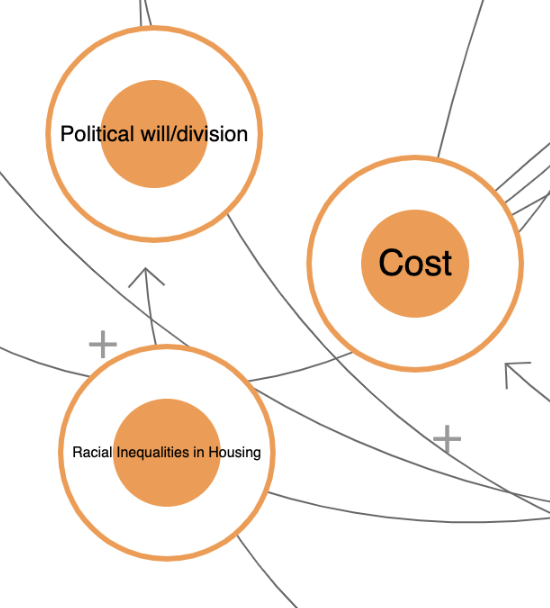

It is important to recognize that even though there are solutions to the problem, there are also barriers (orange circles) that could impact the likelihood of solution implementation, as well as increase the consequences related to the urban heat island. First and foremost, the cost is a huge issue. With any solution, someone must pay for the technologies and enhancements that are requested. Second, political will and division play a direct impact on the impacts of heat islands. Even with stone-cold facts that suggest that there is a problem at hand, an individual’s choice to act may still lay in their political standing and the extent to which they are committed to supporting a specific initiative. Issues of climate change, green technology implementation, and changes in urban environments are all components that may be impacted by politics. Finally, the social component of racial inequalities in housing is a barrier to finding solutions for the urban heat islands. Historically, individuals of color have experienced unfair housing and lending, which had led to disproportionate impacts on this group of people as they are more likely to be the ones in these urban environments. All of these factors must be considered since they are connected to the various solutions and effects related to heat islands.

After completing the systems thinking exercise, it is clear that there are many causes, impacts, solutions, and barriers that are interconnected. The problem is quite complex and features various stakeholders that must be considered when attempting to address the issue. Nonetheless, it still stands as an important problem to address as the population continues to advance and humans look towards renovating metropolitan areas to ensure proper and equitable living conditions. Whether it be to take part in planting vegetation, supporting the development of green infrastructure, or supporting movements that aim to reduce and mitigate the effect of urban heat islands, there are many opportunities at hand.

Next -> Individual Action

Endnotes

1. Urban heat islands. (2021, July 14). Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://medialibrary.climatecentral.org/resources/urban-heat-islands

2. McMichael A. J. (2000). The urban environment and health in a world of increasing globalization: issues for developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78(9), 1117–1126.

3. Health in a world of extreme heat. (2021). The Lancet, 398(10301), 641. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01860-2

4. https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/using-green-roofs-reduce-heat-islands

5. https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/using-cool-roofs-reduce-heat-islands

6. https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/using-cool-pavements-reduce-heat-islands